I’ve been thinking about how we can deploy a safe, zero-trust and upgradeable TEE setup in the short-medium term. Reason being that there’s a lot of super interesting use cases to be run already that would benefit from a trustless tee setup (e.g financial, policy based agents, privacy, etc).

In this writeup I propose two things:

- the ZTEE ledger: a decentralized store that tracks history and ownership of the chips to guard against trojans, core idea is similar to Quintus’ decentralized attestation services idea.

- NB: a subset of this section (on the very bottom of the post) is dedicated to explaining why an FBAS works best in this scenario but it’s not necessarily required to understand the overall idea.

- how to combine the ZTEE with redundancy techniques like secret masking and quorum rotation to guards against physical attacks.

As highlighted above, the design I’m proposing is meant to be easily upgradeable and integrated along with new techniques that are being researched regarding non-destructive testing, trojan resistant circuitry, non-tamperable key generation and storage, etc.

The ZTEE Ledger

Why?

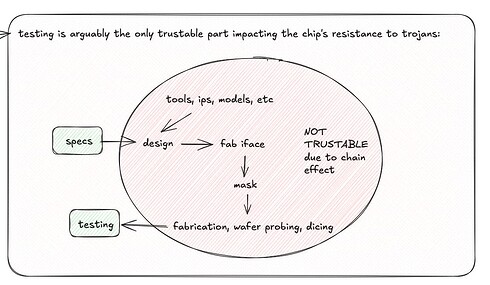

The supply chain is one of the discussed problems when talking about trustless TEEs, in fact the manufacturer itself can only trust their specification and the testing phase:

As a result, we focus on what’s at our reach as non manufacturers: the testing phase. Thanks to recent research towards non-destructive testing, chips can be tested and subsequently used and sold to perform trusted computations. There also is some promising research towards trojan-resistant circuitry (Private Circuits III: Hardware Trojan-Resilience via Testing Amplification proposes a generic IC compiler that turns circuits into trusted master circuit and untrusted non-connected sub-circuits and xor the results to aid trojan detection within the manufacturing, I discuss this a bit more in the original post draft).

The point is that there’s research towards non-destructive testing or open and tamper resistant manufacturing and independently of how it evolves and what becomes the standard, I think we need (think because I’m not fully sure, looking forward hearing suggestions or criticisms towards this idea) a mechanism to track chips and keep each party involved with their security to be also cryptographically accountable for their safety as well as allow everyone to be able to deterministically categorize a chip as verified or not, hence the ZTEE ledger proposal.

What

I propose a sketch of a framework to deal with the above and later mix the masking techniques (which I believe to be the most effective way to counter and discourage hardware attacks in general) along with said framework to prove that we can achieve sufficiently trustable TEEs today in an easily upgradeable setup that can be easily adapted as newer detection technologies emerge (both in verification and manufacturing).

The framework consists of 4 non exclusive actors:

- operators.

- chip proposers.

- chip verifiers.

- chip buyers.

The operators are reputable entities (orgs or community members) operate a ledger that tracks the ownership and verifiability and rely on a secure consensus mechanism to ensure the ledger changes safely. We could either inherit the security from an existing layer (e.g Ethereum L1, etc) or setup our own network. The latter option might actually be quite promising considering the characteristics we’re looking for regarding efficiency and consensus. More about this is discussed towards the end of the post.

How does the ZTEE Ledger Work?

Independently of the underlying consensus we choose for the decentralized store, the idea is to have operators define their own quorum clusters. I recommend reading the FBAS section to understand quorum slices, trust intersections and why are important.

Such quorum slices effectively define the level of trust among the involved parties, which can be inherited by the functionality itself. At a high level, this is the basic workflow I thought of:

- Proposers P_{1, 2} trust other operators O_{2, 3, 6} which happen to be verifiers V_{1, 2} and an external observer (could be a trusted community member or organization). NB: Trusted Operators will also trust other participants, this is ignored in this example for simplicity.

- P_2 proposes a new chip C_n (and trusts quorum/underlying consensus to validate or confute this operation).

- Chain randomly assigns C_n to be verified among one of the verifiers that are in P_2's quorum (Note, it’s not necessarily strictly the verifiers that P_2 explicitly trusts due to transitive trust connections), let’s say V_1. At this point a dispute between C_n and the V_1 is started, and the two parties bring comms off-chain

- When P_2 and V_1 are done (best case scenario, V_1 has been able to test and verify C_n) the dispute is completed and the necessary reports are uploaded by both parties. If there have been any complications in the middle, P_2 and V_1 can close the dispute as incomplete each submitting a report as to their reasoning. Social consensus will then take the appropriate measures to warn either P_2 or V_1, downgrade them in the trust they’ve been assigned in the consensus, or even directly remove them from the quorum causing permanent and cryptographically verifiable reputation damages. NB: as with step 1 and 2, the quorum/consensus chooses to validate or confute these operations.

- Once there’s cryptographic proof that V_1 tested C_n of P_2:

- if the chip was verified, it’s set as pending. I also like the idea proposed in ZTEE: Trustless Supply Chains - Trustless TEEs - The Flashbots Collective to randomly take samples n times to reduce the probability of P_2 and V_1 being in cahoots to put an unsafe chip in the market (the probability is already quite low depending on the quorum size considering the introduced randomness).

- if the chip was deemed unsafe by V_1, it’s doubtful that the dispute was completed as successful (we could merge this directly in step 3 actually), but in any case, P_2 can check and resubmit C_n to be reviewed if they believe V_1 has made an error. Again, social consensus does its job here, if a proposer continuously confutes their quorum’s verification, they will be excluded or their relevance decreased (e.g low in the priority of proposers the verifiers have to verify).

- Similarly as in the original ztee gov design, buyers can express interest in buying a chip among the ones that are pending. This is randomized to protect the buyer’s users (also from the buyer itself). A new dispute is opened between the verifier(s) and the buyer.

- Once the buyer has received the freshly-reviewed chip from V_1, they can post the necessary proof to the ledger and the dispute is successfully closed. This emits cryptographic proof that C_n, verified by V_1 is owned by the buyer starting from t. Applications running on TEEs can later also rely on t for internal logic to prevent against physical attacks that might require several months if not years to complete (more on this later).

ZTEE + Masking

Since the “ZTEE ledger” offers a deterministic way of knowing that a certain chip was validated, we can embed this functionality within the code that is running within the TEEs. This is particularly useful if more than one chip is involved in our app. For example, a very robust design for a TEE app would be masking through secret sharing and/or requiring to rotate the quorum (and secret) after a certain expiration determined by reading the ZTEE ledger for the current chip.

Interacting with the ZTEE ledger would allow checking a point in time t until which the chip’s integrity can be trusted. Considering that attacks for trusted computing bases take several time and monetary resources, secret masking itself can be really effective, and becomes unbreakable (I believe) when paired with chip rotation since the new chips will also be freshly verified by the “ZTEE ledger”.

In this situation, if we go for a minimal FBA based blockchain, the simplicity and negligible (for how low they are) compute requirements of verifying and fetching the supply chain’s state becomes a fairly big advantage.

Secret masking + quorum (and secret) rotation with chips that can (semi-)deterministically be deemed as zero trust execution environments thanks to the ZTEE ledger (for tracking and verification) is a very resilient (and potentially robust) framework that I believe brings very high levels of security for all current use cases that we are looking forward to implementing with TEEs assuming the software is correctly written.

First Prototype: Centralized TEE MPC cluster

A feasible first prototype could be to have a centralized cluster of co-located TEEs that have all been verified by the ZTEE ledger that implements MPC for masking, quorum rotation and which allows developers to deploy TEE containers. This would:

- Lower the amount of overall chips verified by the ZTEE ledger. Chip verification takes time and is expensive (even if non destructive testing is promising also for this), sharing chips for different containers makes sense considering the first workloads will likely be very light (financial, agents, etc).

- Mitigate against physical attacks if quorum set is transitioned (those chips can later always be re-used/re-verified) since there wouldn’t be the time and it’d be really expensive to compromise all the chips masking the secret (approx 1M per chip it seems). I think masking also gives us much more chip verified expiration if we rotate quorums wisely.

- Physically co-located rig of chips would make MPC feasible efficiency-wise as RTT would be very low (microseconds?). This is the main reason why I’m thinking about MPC.

- Make up for an incredibly robust and safe infrastructure to deploy the TEEs to, deployers could also specify the redundancy required. I think that even just a single TEE that gets rotated say every 10 months or more would suffice in safety for most use cases.

Main questions here are:

- Is the cost-to-attack lower if the chips are co-located?

- How big is the RTT reduction by having the cluster centralized (my guess is from tens of milliseconds to microseconds?)

- How to best implement quorum rotation? I think we can extend the chips’ lifetime with random rotation almost linearly with the number of chips in the rig, there probably is a number of chips N at which the attacker has probability on their side so we might want to enforce a more drastic change of the view set.

- Who control the rig? Why would they spend money to set this up? How do they make money?

- Not really a question, but the centralization of the chips makes it much easier to shut down multiple applications at once, apps should have an escape hatch on-chain to reset user state (there’s a few ways to do this).

Some notes

Randomness

There’s probably a lot to discuss and lots of consensus mechanisms to inherit from to deal with adding randomness to the protocol. This is needed if we implement random sampling and for random chip-buyer assignation. The very same source could also be pulled directly within TEE apps (or not) to deal with quorum rotation if there are idle workers rotating vs just adding new ones.

Quorum Participation

- proposers are not necessarily manufacturers, even though having manufacturers themselves as proposers would be good as the latter likely have much more reputation (particularly, bigger consequences) to loose.

- node operators that are not chip proposers, verifiers or buyers don’t actively participate in the framework but are rather important to helping shape the quorum slices if they are respected companies or community members.

- buyers can choose from which quorum to buy the chips from. The bigger and the more trusted the quorums are, the more buyers will be looking forward to buy from that quorum, increasing profitability for both verifiers and proposers.

- there can be multiple independent quorums, which ones to trust is on the buyer and on the TEE applications (if they hold logic that deals with the ZTEE ledger).

On monetary incentives and payments

- Since we talk about accountability, the trickiest part here is make sure the incentives are set up correctly. There’s still open questions about that. I personally am against participants posting monetary collateral since imo the best design is based off of programmable social consensus, monetary collateral would either need to be prohibitively high and actually less safe. This still means that buyers being ok with paying more for verified chips is going to happen, I just don’t think we should be placing collateral as an on-chain requirement, rather only keep the business between the interested parties. E.g proposer tells verifier they will pay $A for the service upon proposing, and if the verifier encounters any issues with the proposer not paying or whatever they can deal with it like all business currently do + if either party does not behave correctly their reputation is slashed by social consensus. idk if that makes sense.

- the protocol doesn’t care that any value transfers occurred among the parties, that part is completely off-chain and the protocol is agnostic to it it just cares that both parties resolved or not, if not the quorum will do its job. We could however keep some on-chain information regarding the agreements (e.g for pre-agreeing on proposed prices).

Setting up the ZTEE Ledger, FBAS and Trust Clusters

Here I expand more about implementing a secure FBAS (Federated Byzantine Agreement System) for this purpose below, talking about trust slices, programmable social consensus, efficiency, and more.

Below are some points as to why we might want to consider operating our own chain.

Efficiency

These nodes could be insanely cheap and easy to run given the simplicity of the messages and state, and participating entities are not obliged to necessarily deal with cryptocurrencies. This becomes a significant advantage if the TEE needs to obtain data from the chain by running a light client (this one would be really light).

Consensus

This allows all parties involved in the ownership of the chip (proposers, verifiers, buyers) to be part of the security of the supply chain being tracked, whereas relying on another layer requires all parties to trust the underlying consensus without likely having a say in it due to the high requirements.

The counter-argument is of course that it likely is more feasible to attack such quorums as opposed to a sufficiently decentralized blockchain, even if the parties involved are not necessarily those upholding the decentralization.

Anyways, regardless of the underlying consensus, the end result would be to have a programmable social consensus layer among knowledgeable parties that place varying level of trust in the operators (including those involved in the chip’s ownership). That said, since we’re trusting a quorum of operators including verifiers and proposers, then we can also trust a set of node operated by them (i.e “our own chain”). As a last resort, we could also make TEE node execution a requirement (again the nodes would be really light).

FBAS

The main idea of a FBAS is that each node defines its own quorum slices, being the set of nodes that they trust to reach consensus. Or better, the quorum slice is a subset of the quorum that convinces a particular node (the trustee) of agreement. A node being able to select their own quorum slice set is what differentiates FBA from other byzantine agreement protocols allowing quorums to emerge from local choices, meaning that each node can choose who they trust based on reputation or financial arrangements and the intersection will form the quorum, being the set of nodes sufficient to reach agreement.

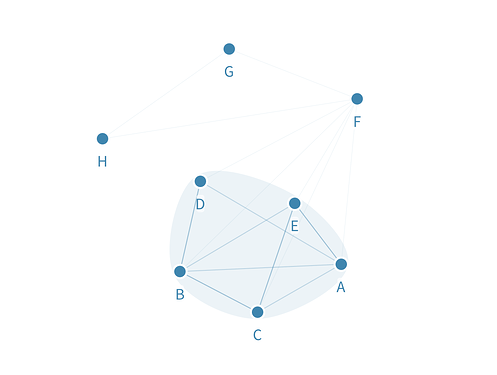

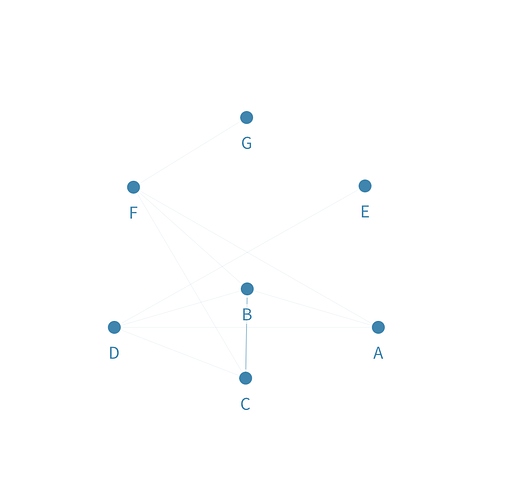

For instance, let’s say we have nodes A, B, C, D, E, F, G, H with the following quorum slices:

Node A trusts: [A, E, D]

Node B trusts: [A, B, C, D]

Node C trusts: [A, C, B, E]

Node D trusts: [B, D]

Node E trusts: [A, E, C, B]

Node F trusts: [A, B, C, D, E, F]

Node G trusts: [F, G]

Node H trusts: [F, G, H]

If we do an intersection of trust, the resulting network looks like the following:

Note that:

- The nodes in the quorum that decide the state of the ledger (top tier) is the one highlighted in light blue, i.e the result of the trust intersection of the nodes: Q = {A, B, C, D, E}. This is a classical PBFT system.

- Even if a middle tier node like F does not actually have any say in finalizing consensus, it doesn’t mean they cannot participate in the network.

- The transitive trust property is respected, e.g A does not directly trust C but are part of the same top tier quorum.

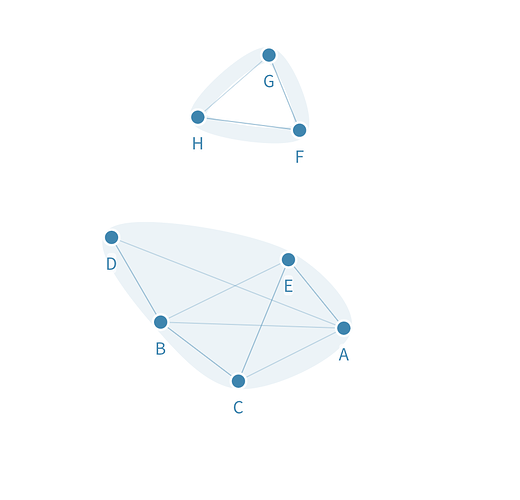

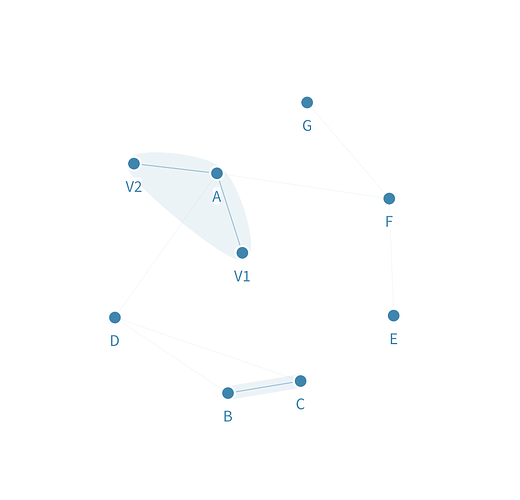

In the above situation, node F is the link between nodes H, G and the top tier nodes. If for some reason F stops trusting nodes A, B, C, D, E then this effectively splits the network and we now have a second group of nodes H, F, G that can finalize consensus among themselves since they’re not awaiting for the other nodes to sign off consensus anymore, as shown in the following image:

Whether to now trust HFG or ABCDE is up to social consensus, and we could theoretically see both being trusted by different kind of organizations and use cases.

How does this apply to chip verification?

Above I describe a mechanism to reach consensus, which in case the ztee ledger was based on an existing blockchain would not be needed. However, while describing the ztee ledger I mention that the functionality of the ledger (i.e chip verification) can inherit properties from the trust slices to basically decide how proposers, verifiers and buyers are matched. In my example, P_2 must declare a set of verifiers (directly or indirectly) that they trust, among which the chain will randomly sample one to verify P_2's chip. Just like in the above quorum configuration F is not part of the top tier but can still participate in the network, new proposers that don’t have reputation can propose chips to verifiers that they have chosen to trust. Similarly, buyers need to declare (again, either directly or indirectly) which proposers and verifiers they trust.

Example 1

Imagine a quorum where A, B and C are verifiers (that trust each other) that proposers D and F trust. Buyers E and G respectively trust proposers D and F:

Both proposers D and F are free to participate and launch chip verification, and due buyer-chip randomization and due to how the quorum is configured:

- G could get D’s chip even if D is not in their trust slice.

- E could get F’s chip even if F is not in their trust slice.

That’s because the verifiers in the top tier are the common denominator that ultimately decide how to assign chips.

This is the happy path.

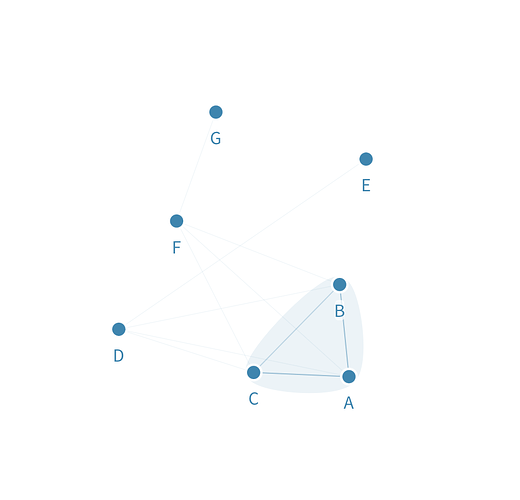

Example 2

Imagine that verifiers B and C both stop trusting A without any apparent reason because they are in cahoots with proposer D which wants to have a chip with a trojan verified. This causes both buyers G and E to potentially buy chips that have 50% of probability of having a trojan since D’s chip would be maliciously verified (BC would be the only ones in top tier):

In the meantime, A revokes the trust they had for BC and has onboarded new reputable verifiers V1 and V2 and formed a new completely separate quorum that doesn’t require BC’s signature (NB: V1 and V2 don’t trust each other but the common denominator is that they trust A). Non-malicious proposer F can now revoke trust from BC too, causing buyer G to be safe in the new quorum, and all non-malicious buyers to migrate trust to the new quorum:

Note that in the new setup:

- Verifiers BC have lost significant amounts of reputation (or more) for having explicitly plotted and tried gaining control of the quorum.

- D can still propose new chips.

These examples are both oversimplifications but should make clear the reason why I think an FBAS works great for the ztee ledger:

- Verifiers are the most important entities, and a minimum trust intersection between these is required (the common denominator could also be a reputable non-verifier organization or community member). We don’t want anyone to casually be able to become a verifier.

- Buyers can choose which quorums to trust with their purchase, and verifiers (i.e top tier) are again the ones that need to sign off on the chip, regardless of whether the buyer directly trusts all verifiers or proposers. Users and apps running on TEEs can easily check which was the quorum that signed off on the chip’s validity.

- Anyone can propose a new chip, this is not a membership only club.

- The creation of multiple ztee ledgers is possible.

- Proposers, buyers and verifiers do not need to review all of the entities they trust simplifying the “who-to-trust” decision, the end result is dynamic and depends on all of the nodes’ local choices. There is no central committee that decides which are and which aren’t the verifiers.

Some challenges are in deciding the thresholds for randomization. I assume the implementation will actually want proposing and buying to be split and not p2p initiated. This means that there probably needs to be a pool with at least n chips waiting to be proposed (or already verified?) before the buyers can purchase (or vice-versa i.e a set of buyers willing to buy before proposers can propose?). Another challenge is the high proposers-verifiers ratio that will pretty surely come up especially with proposers being free to propose without needing to be trusted. If we introduce random sampling, malicious partially anonymous (no proposer will in fact be anonymous since a lot of activity is off-chain) proposers could have a probability of getting a malicious chip on the ztee market. If we don’t introduce random sampling, wait queues for chips will be too long even if more verifiers get onboard due to the increased demand. We could find a middle-ground solution where random sampling is only enforced for trusted proposers that verifiers trust as they have good track record while new proposers have to wait longer and all their chips need testing. Proposers who are reputable entities will naturally be earning and proposing more due to shorter chip approval times, leaning towards an ideal setup that is however not permissioned.

Is this too convoluted to be practical? Also, note that this document was not reviewed and is written to incentivize a discussion around the topic, not to directly propose a standard ready to be implemented, so there might be logical errors too! Feel free to point any of those out or let me know if there’s anything missing. (I will be updating the document as new ideas emerge)